Artist

statement

Artist

statement

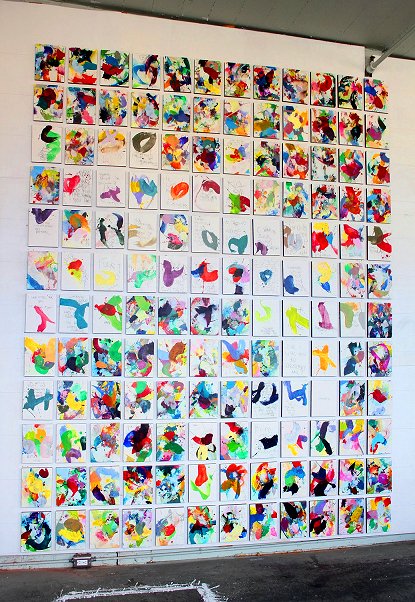

Pretty Mess with Words (2010)

by Dorothy Goode

My life fell apart last year. As breakdowns go, this one

was enviable (if you are anything of a romantic, which I am)

and unexpected. Once in trouble, however, I set to work.

There is nothing like having one’s cells ripped apart and

then re-cemented to make for fresh curiosity. “Material”

becomes inevitable—which brings us to the by-now terribly

familiar question: What is the difference between

fact and fiction?

I am long accustomed to viewing my life as a partially

coherent, not-very-well-written novel, and my artwork has

been a partner in this. I do like words. I like how they

work. I like how cunning they are, and insidiously

influential. I even like how they look when handled by hand

and allowed to spread out like momentarily tired,

sharp-toothed beasts. So when the crisis hit, I began to

write things down all over 144 accidentally book-sized

panels, specially prepared for them and meant to set the

stage for yet another batch of colorful, acquiescent

abstract paintings.

Initially I thought to call the series something along the

lines of The Jesus Prayer. This was satisfying to my

psyche, given the astonishing amount of guilt I was

experiencing, but was also rather disingenuous, as I have no

relationship to Jesus whatsoever, unless you count an

unnerving tendency to talk to him whenever I walk into

humble Mission churches. So I gradually let the idea of

publicly proclaiming myself a sinner go, and settled on

calling the work, once completed, exactly what I saw it to

be: a pretty mess with words.

This wasn’t the first time I had written on a surface as an

underpainting, but it was the first time there was a

unifying theme to the writing. Also, some of it remains

legible—and the subject matter is more than a little

narcissistic. To write personal information on a surface

meant to become a painting is a dubious thing. It makes one

feel, subtly, already more significant than one was before.

The surface has become the rack on which one can either

stretch oneself or clothe oneself, spilling color all the

while. And it changes the painting game. It makes it—the

game—just a bit more dangerous, rather like putting a new

edge on a well-used knife. But like the knife, it is simply

a tool.

RETURN TO

MAIN MENU

Artist statement